Headphoning It In: That ’70s Sound, starring Santana

November 1, 2019

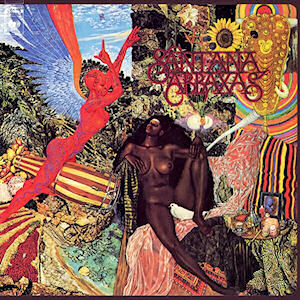

1970: Forty-nine years ago, after already solidifying legendary status and achieving major Woodstock success, Santana released Abraxas, an unassuming, career-defining, nine-track masterpiece. Its conceptual simplicity is countered by unrivaled instrumental mastery. For an album with such few lyrics, the music is still able to speak for itself. The complex layered album art is an even greater sublime reflection of the beautiful madness that makes Abraxas as powerful as it is.

The album’s opener, “Singing Winds, Crying Beasts,” could not be a more fitting name. Wind chimes, bongos, and wailing guitars are peppered throughout this instrumental track. Each sound fades in and out from one ear to the other and is meditative in nature. As introspective as it is on its own, “Singing Winds, Crying Beasts” can be boiled down as being the glorified introduction to none other than “Black Magic Woman.”

Santana’s cover of a Fleetwood Mac staple turned rock on its head with a flattering bossa nova twist and electric guitar finesse of which could only be accomplished by a seasoned musician. Santana’s soft vocals break through the hypnotic rhythm with haunting precision. As if “Black Magic Woman” didn’t have enough of an iconic guitar solo, its outro, “Gypsy Queen,” allows for Santana to show off even further as it bridges together the track’s jazz and rock influences.

“Oye Como Va” is the Chicano rock song. A choir of voices repeats a short refrain that’s so simple yet undoubtedly memorable. The rhythmic guiro, with its signature scraping sound, elevates the percussion even when it’s overshadowed by more melodic elements of the song.

The jazz fusion number titled “Incident at Neshabur” begs the question of what actually happened in Neshabur for such a jarring piece of music to exist. A commanding piano reigns supreme until it’s bluntly cut off by an even more domineering electric guitar. The song is a mixture of a million different sounds, and just as you feel comfortable within one state, the energy level switches up again. The wailing horns and freestyled piano draw heavily from bluesy influences to produce the most dynamic track on the album.

Repetitive and bongo-heavy, the record’s midpoint, “Se a Cabo,” warns the listener from the beginning that it’ll be over before it even begins. The instrumental’s fiery maracas and entrancing percussion are unrivaled by the repetition of the only lyrics, “se a cabo,” before fading into the next ambitious track.

“Mother’s Daughter” is easily the most underrated track off Abraxas, and fully embraces the auditory classic rock aesthetic. It is one of few that actually follow a standard sonic formula, and has a whole three verses intermixed by electric guitar solos. Santana’s voice is breathy and raspy, exuding passion with every lyric. It’s electrifying, respect-demanding, and undoubtedly my favorite song from the album.

“Samba Pa Ti” jarringly contrasts with the previous track. It embodies the signature despair and sadness present in Motown blues hits. Sans lyrics, once again, the somber wailing guitar replaces any human voice, telling a compelling story of tragedy and heartbreak.

“Hope You’re Feeling Better” spices up the record before its confounding bossa nova end in “El Nicoya.” Passion and flare run rampant with superlative instrumentation that bleeds with emotion. As a last hurrah, the closing tracks contrast yet blend together without question, and they are a perfect end to such a vibrant album.

The question remains: why treat Abraxas as something special when it’s just another half-century-old rock album influenced by psychedelia? Well, in just two words, because of Chicano rock. Whether referring to Santana, the group, or Carlos Santana, the man himself, Chicano rock is a genre that’s more American than we probably realize. The genre, and the Latin artists who pioneered it, bends jazz and rock and soul and blues all into one. Musical self-expression and bold experimentation were beyond encouraged, and this revolutionary era in music history influenced daring new sounds that are still praised, mimicked, and immortalized in the present day.