For several weeks, the song “Walk My Walk” by Breaking Rust topped Billboard’s Country Digital Song Sales chart, alongside a number of songs by Caine Walker. All of these charting songs were written and performed by AI, becoming part of a growing trend of AI “artists” slipping into the mainstream music industry.

What bothers me about this isn’t just that AI is making music (and ripping off who knows how many unnamed artists), it’s that music has always been such an innately human thing. For as long as we’ve been able to communicate, humans have created music– and not just for entertainment, but for storytelling and resistance, or to express emotions such as love and grief. To remove humanity from music is to remove its essence. If a song doesn’t communicate with its audience, can it even be considered music?

And if you look back on music, especially within America, it has always been political. Decade after decade, some of the most influential and era-defining songs were written as a form of protest or social commentary. Hip-hop and rap, punk rock, post-punk, folk, reggae, soul, and funk are all inherently political genres of music, sharing origins in marginalized communities and a strong anti-establishment ethos. Artists like Public Enemy (“Fight the Power”) and N.W.A (F*** tha Police) directly confronted state violence and systemic racism, while Queen Latifah’s “Ladies First” celebrates the strength and unity of women in the face of oppression.

No matter the genre, the process of creating music is incredibly intimate–when artists write honestly about their own lives, they naturally invite broader conversations about the culture and systems surrounding them.

Personally, I’m an avid fan of late ’60s and ’70s music. Music was used at this time, as it has been throughout history, as a form of resistance and advocacy in the face of political upheaval and disarray across the world.

American music from the ’60s was, in many ways, a protest movement against the Vietnam War on its own. Creedence Clearwater Revival was a leading advocate against the Vietnam War, with songs such as “Fortunate Son,” “Down on the Corner” and “Bad Moon Rising.” John Lennon calls for an end to the war in “Give Peace a Chance,” while Bob Dylan discussed its societal impacts in “The Times They Are a-Changin.”

Countless songs from this era carry unmistakable political undertones, even if the artists themselves choose to leave the meanings open-ended. Don McLean’s “American Pie” is clearly a commentary on the death of innocence in America and the Vietnam War, yet McLean consistently resisted rigid interpretations of the song. Similarly, Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth” is widely embraced as an anti-Vietnam War anthem, despite Stephen Stills writing it in response to the Sunset Strip Curfew Riots. Regardless of their original meanings, both songs became staples of the antiwar movement.

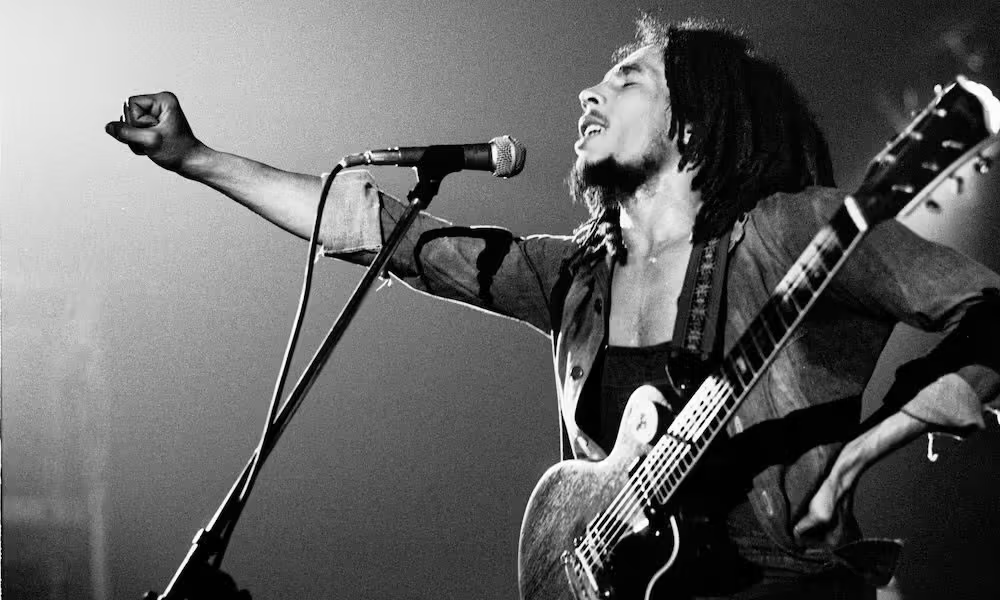

Artists in the ’70s continued to use music as a form of advocacy across the world. Bob Marley’s “Get Up Stand Out,” written after a trip to Haiti, calls for people across the world to rise up and fight against oppression and injustice. U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday” was a blistering condemnation of the Bloody Sunday Massacre in Northern Ireland that discusses how violence and war are destructive and pointless. Meanwhile, in America, Stevie Wonder was topping charts with “You Haven’t Done Nothin’,” a searing indictment of President Nixon released just two days before he resigned.

By the ’90s and 2000s, politically-minded music was no longer confined to underground or counterculture scenes– rap, pop, rock, and post-punk all carried messages that reflected the social and political unrest at the time. Rage Against the Machine fused rap and metal into a relentless call against systemic injustice (“Killing in the Name of”), corporate greed (“Sleep Now in the Fire”), and government corruption (“Bulls on Parade”). Green Day similarly produced an unending discography of songs calling out political corruption (“American Idiot”) and the U.S. war machine (“Holiday”). At this point in time, politically-centered music was mainstream.

So how did we get to where we are today? That’s not to say music is no longer political, but it’s once again considered counter-culture. It’s an interesting reflection of how we, as a country, have regressed on our societal advances. We have somehow returned to an openly exclusionary society, as we elected a president who ran on an explicitly racist, misogynistic, anti-LGBTQ+ campaign. It’s a stark contrast to earlier eras, when moments of national crisis often ignited waves of politically-charged music.

Yet, of course, moments of political expression persist: Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime performance was a brilliant reminder that music is a powerful vehicle for protest. On one of the most commercially driven stages in America, Lamar used his platform to directly confront systemic racism and America’s cultural and political divide through the metaphor of a “rigged game.” He also explicitly referenced Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” evoking musicians’ enduring call to fight against systematic injustices.

Looking back on the history of music, it’s clear that it has always been a mirror of society, a way to confront what’s wrong and celebrate what’s right. In times of despair, humans have often turned to art as a way to express discontent, and music has proven to be an enduring form of protest. Yet, in today’s era of political turmoil, we see both a decline in politically charged music and a rise in AI-generated songs. We cannot allow AI to take the place of human expression in music– especially at a time when our voices are so necessary. If we continue to prioritize mass production and profit over the creation of art, we risk losing an essential part of what it means to be human.