The Looking Glass: Trust’s "Joyland"

April 1, 2014

The recent release of Joyland marks a certain revival of Robert Alfons’s creative project Trust; in Joyland we are thrust into a movement forward, an unfolding from an establishing parameter ÛÒ one sketched out in his first album TRST ÛÒ to a joyful and affirming orchestration which renders visible the distinguishing features of Alfons’s musical talent. Thus, we can come to see that Alfons’s entire acoustic, in Joyland, is based upon the sharp contrast between one’s personal conception of self-confidence, and one’s absolute plea for authenticity. The movement away from TRST is undeniable; it is, in the most basic sense, at the center of Joyland; suffice it to recall the experience of closure at the end of “Sulk” from TRST: the landscape of the album is slowly unwound; the album is all but reverted back into a more basic substratum of experience; the tempo builds, the melody unwinds. Let us focus our attention, then, on the experience of Joyland. What precisely does this album intend for us to experience? Alfons’s interpretation of this album is the following: Joyland is an eruption of guts, eels, and joy.” What is a striking difference between Joyland and TRST is how Alfons’s voice is articulated as the middle term of Joyland ÛÒ that is, his voice, unlike melody or the specific lyrics bound to the voice, is what weds and marries our experience of the album to the often distorted, crawling, and wrinkled melodies and tempos found throughout Joyland. Gone are the places of profound enunciation and clarity heard in TRST; the voice here is masked and mired in a web of distortions.

[Check out the song “Capitol” here]

Yet, although we might have expected the notion of the voice to be a secondary effect of Joyland, ÛÒ which was clearly the case in TRST ÛÒ to be completely secondary would require the voice to be subverted and dependent on the primary aesthetic of the album ÛÒ that of the melody, the tempo, lyrics and so on. The truth turns out to be more complex, however. For, while Joyland distinctly reduces the overall intelligibility of Alfons’s voice, we nevertheless are guided and welcomed by Alfons’s distinct and uplifting voice; in a way, we are committed to the momentum of Alfons’s voice, in it we trust and gain access into the very universe that Trust has sought so actively to construct over the past few years. Indeed, as Alfons’s commented in many recent interviews, this album was more of a byproduct of his touring process than anything else. Thus, as Alfons experienced Trust as Trust (that is, experienced himself as the perception that we all possess and view Alfons as being when we locate him within a certain social circumstance, or musical venue), Joyland becomes the trace, path, or mark of that journey, of Alfons movement into society’s perception of an Trust itself. And this is the real, actual feature of Alfons’s musical talent in Joyland: the voice, no ÛÒ more generally now, the body of the work is suspended into and affected by the hidden undercurrents of the melody and tempo that we bring to bear on this album; we (as a certain experiential parameter) move and create the discordance between Alfons’s voice, and its flight through the chaotic environments that are enunciated by and through Joyland. Of this, we may ask when listening to “Icabod:” Why is there such an emphasis on the repetition of melody and lyrical content? Why does the effect of Alfons’s voice seem to hover over and behind these iterations?

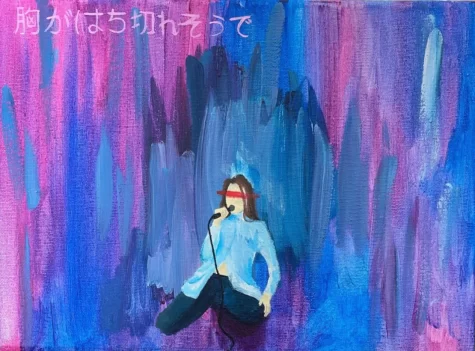

This is all to say that the experience of Joyland is not an easily understood phenomenon; it is not a conventional opposition between rhythm and vocals (where one weds melancholic ideations with an uncanny tempo to perhaps propel one towards a general feeling of sadness, despair, and so on). Rather, and this is the real brilliance of Alfons, Joyland is a profound attempt to localize us into the very environment which propelled and compelled Alfons to create this album ÛÒ to see how his perceptions of himself and our perceptions of him, the environment we both imagine to have while at a Trust concert, when playing a Trust song at a party, and so on. Therein lays the fundamental feature of Trust’s latest achievement: an uncanny union between the details of our particular experience with our overall perception of Trust as a musical phenomenon. Of this, one must simply watch the music video for “Heaven” and then the music video for “Rescue, Mister:”

Of this experience, it is also impossible to achieve any inter-textual analysis, one which we could provide a deeper cultural or linguistic insight or analysis. Thus, we are only given, in the most basic sense, the singular experience of the album. The support for this album ÛÒ that which makes it an album ÛÒ does not arise from the inter-textual engagement between the vocalized progressions of one album to another; rather, it is the relationship of our singular experience of the album with our previous experience with Trust’s other album that demarks it as something different from Alfons’s previous works. The context in which we receive the album has most certainly changed ÛÒ we may have achieved a new experience with Alfons, locating ourselves into the many popular venues that will play his music within a music set. But the experience of listening to Trust certainly remains a powerful affliction to us as listeners ÛÒ we are forced to confront the very parameters of our experience when listening to Joyland, drawing and relating it to our previous experiences without a moment of inter-textual analysis or understanding. It is simply an experience that can only be understood in terms of experience itself.